Le Cabinet Medici a le plaisir d’avoir été cité parmi les dix plus beaux cabinets créés durant l’année 2020 par la Lettre des juristes d’affaires du 21 décembre 2020, n° 1472.

Valence Borgia, associée du Cabinet Medici et membre du Conseil de l'Ordre, est intervenue dans le Podcast « Travail (en cours) » de Louie Media sur le présentéisme dans les cabinets d’avocats le 17 décembre 2020.

Le podcast est disponible sur le lien suivant : https://louiemedia.com/travail-en-cours#:~:text=Comment%20le%20pr%C3%A9sent%C3%A9isme%20r%C3%A9siste%20aux%20confinements&text=Le%20pr%C3%A9sent%C3%A9isme%2C%20en%20France%2C%20est,sondage%20Glassdor%20d'octobre%202019.

Valence Borgia, associée du cabinet Medici, est membre du jury du « prix Gisèle Halimi », concours d’éloquence organisé par la Fondation des Femmes « pour dénoncer le sexisme par le verbe », aux côtés de Giulia Fois, Julie Gayet, Nathalie Roret, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et Yseult.

Ce concours d’éloquence, qui porte sur les droits des femmes, sera diffusé le lundi 21 décembre à 20h sur Facebook.

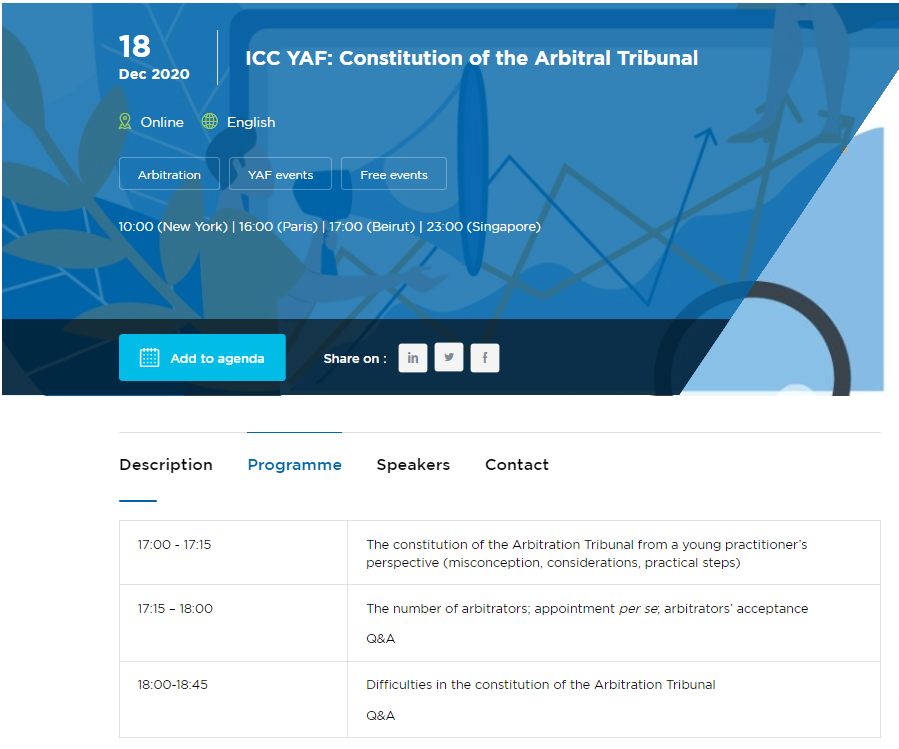

Ce vendredi 18 décembre 2020, de 17h00 à 18h45, Marie-Laure Bizeau, associée du cabinet Medici, interviendra aux côtés de Nada Sader, associée chez Derains & Gharavi au Liban, et de Nadine Kozma de chez Alem & Associates au Liban, sur le sujet de la constitution du tribunal arbitral dans le cadre d’une conférence organisée par le ICC Young Arbitrators Forum.

Pour retrouver le programme et vous inscrire à la conférence, suivez ce lien : https://2go.iccwbo.org/icc-yaf-constitution-of-the-arbitral-tribunal.html/.

La réforme du droit français de l’arbitrage aura dix ans le 13 janvier 2021. Pour célébrer cet anniversaire, le Club des Juristes organise une conférence durant laquelle Caroline Duclercq, associée du Cabinet Medici, interviendra sur « L’apport et la place des textes et de la jurisprudence depuis le décret du 13 janvier 2011 », aux côtés de Thomas Clay, Dominique Hascher, et Pierre Todorov. Cette conférence sera en ligne, le 13 janvier 2021, de 17h00 à 19h00.

Pour retrouver le programme et vous inscrire à la conférence, suivez ce lien : https://www.leclubdesjuristes.com/inscription-conference-10-anniversaire-reforme-droit-francais-arbitrage-mercredi-13-janvier-2021/.

Valence Borgia, Marie-Laure Bizeau et Caroline Duclercq, associées du cabinet Medici, sont une nouvelle fois reconnues par le Who’s Who Legal 2021 comme « Futures leaders » en arbitrage. Merci à nos clients et pairs qui participent à ce classement!

La checklist présente les bonnes pratiques, méthodes et outils disponibles pour procéder au choix des arbitres, sur la base de critères objectifs de nature à promouvoir tant l’efficacité que la diversité de l’arbitrage. Pour accéder à la checklist, cliquer ici :

https://cdn1.arbitralwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ERA-France-guidelines-FRENCH.pdf.

Le sondage cherche à explorer les méthodes et les critères employés dans la sélection des arbitres par les principaux acteurs de l’arbitrage, soit les utilisateurs (entreprises), les conseils et les co-arbitres chargés de choisir le président du tribunal arbitral. Pour répondre au sondage, cliquer ici : https://fr.surveymonkey.com/r/T27TLZZ.

Félicitations à nos collaboratrices Marie Eichwald, Zélie Héran et Marie Morier qui ont prêté serment le 13 novembre 2020 au Barreau de Paris.

Bienvenue dans la grande famille des avocats, chères consœurs !

L'équipe du cabinet Medici s'agrandit avec l'arrivée de Marie Eichwald, diplômée d’un Master 2 Magistère de Juriste d’Affaires, D.J.C.E., de l’Université Paris II Panthéon-Assas Université Paris II Panthéon-Assas, spécialité contentieux interne et international de l’entreprise. (plus d'information: https://medici-law.com/notre-equipe#marieeichwaldfr).

Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University), New Law College, Pune's Madhyasthta- The ADR Cell under it's initiative GIADRA- An Oracle for ADR presented it's 13th set of Blogs and Lecture for this week on the theme: "Alternate Dispute Resolution Practices and Rules".

The second blog published under the theme is "UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules: The Pioneer Arbitration Framework" authored by Ms. Caroline Duclercq , Partner Medici Law Firm, (Paris - France) and Director, MOOC, International Arbitration, Paris, France.

Click on the link to read the blog:

http://bvpnlcmadhyasthta.com/uncitral-arbitration-rules-the-pioneer-arbitration-framework-ms-caroline-duclercq/